Nearly 6,000 ISIS detainees were transferred from crumbling prisons in northern Syria into Iraqi custody in a sweeping, multi-agency operation coordinated by the United States. The transfer, which unfolded over just a few weeks, headed off what a senior U.S. intelligence official described as the potential "instant reconstitution of ISIS."

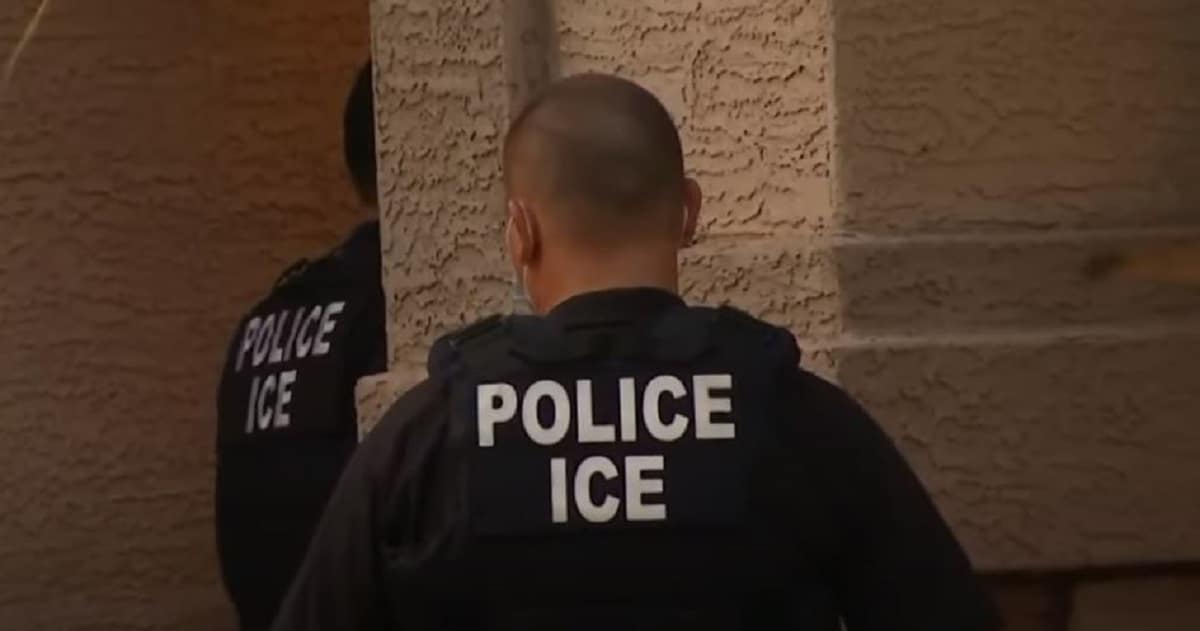

The detainees, characterized by the official as "the worst of the worst," had been held in northern Syrian prisons under the guard of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces. They now sit in a facility near Baghdad International Airport under Iraqi authority, where FBI teams are biometrically enrolling them one by one.

It is, by any measure, a significant national security win executed without fanfare.

According to Fox News, the groundwork started in late October, when Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard began assessing that Syria's political transition could spiral into disorder, creating the exact conditions for a catastrophic jailbreak. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence dispatched representatives to both Syria and Iraq to open early discussions with the SDF and the Iraqi government about removing the detainees before the window closed.

Then the situation accelerated. In early January, fighting erupted in Aleppo and began spreading eastward. The fears sharpened. ODNI stood up daily coordination calls across agencies. Secretary of State Marco Rubio managed the day-to-day policy considerations. CENTCOM surged resources, including helicopters, to physically move the prisoners. The U.S. Embassy in Baghdad played what officials described as a pivotal role in smoothing the diplomatic runway with Iraq.

A senior U.S. intelligence official walked Fox News Digital through the operation:

"Thanks to the efforts… moving in helicopters, moving in more resources, and then just logistically making this happen, we were able to get these nearly 6,000 out in the course of just a few weeks."

The speed matters. These were not stable, well-funded prisons with permanent infrastructure. They were facilities in a war zone, guarded by a militia navigating its own uncertain future. Every day those detainees sat in crumbling custody was another day the math tilted toward disaster.

The intelligence official was blunt about the stakes:

"If these 6,000 or so got out and returned to the battlefield, that would basically be the instant reconstitution of ISIS."

That's not hypothetical. Iraq's own leaders recognized it. The official described Iraqi authorities' understanding that a massive breakout could thrust them back into a "2014 ISIS is on our border" situation. That year remains the benchmark for catastrophe in the region: the year ISIS swept across northern Iraq, seized Mosul, and declared a caliphate that took years of grinding warfare to dismantle.

Iraq did not need to be convinced. It needed a partner capable of executing at speed. The U.S. provided the intelligence architecture, the logistical muscle, and the diplomatic coordination to make it happen.

The transfer itself was the urgent phase. What follows is painstaking but equally critical. FBI teams on the ground in Iraq are working to biometrically identify every detainee. U.S. and Iraqi officials are examining what intelligence can be declassified and used in prosecutions. The State Department is conducting outreach to countries of origin, encouraging them to repatriate their citizens held among the prisoners.

None of this is simple. The detainees represent multiple nationalities. The source countries have, for years, shown little appetite for reclaiming fighters they'd rather pretend don't exist. Whether that diplomatic outreach produces results remains to be seen, but the pressure is now on foreign capitals rather than on overstretched Kurdish guards in a destabilizing Syria.

Meanwhile, a separate and troubling situation is developing. The al-Hol camp, which housed tens of thousands of ISIS-affiliated families, is being emptied. The SDF and the Syrian government in Damascus reached an understanding that Syria would take over the camp. But what "take over" means in practice looks a lot like abandonment.

The intelligence official did not mince words:

"As you can see from social media, the al-Hol camp is pretty much being emptied out."

The official added that it appears the Syrian government has simply decided to let them go free. Children who grew up in that camp are now approaching fighting age. A generation marinated in ISIS ideology, walking out the gates with no screening, no accountability, no plan.

"That is very concerning," the official said.

And it should be. The 6,000 fighters now in Iraqi custody were the immediate threat. Al-Hol represents the longer fuse.

This operation involved no dramatic press conferences, no prime-time addresses, no breathless cable news countdowns. It involved intelligence officers on the ground in October, daily interagency calls through the winter, helicopters moving prisoners across a border, and FBI agents running biometric scans in a facility near Baghdad's airport.

The senior intelligence official called it "a rare good news story coming out of Syria." That undersells it. Syria has produced almost nothing but bad news for over a decade. The fact that an American-led operation quietly neutralized the single largest concentration of ISIS fighters before they could scatter back into the field deserves more than a passing mention.

Consider the counterfactual. Six thousand trained, radicalized fighters pouring out of Syrian prisons into a region already fractured by civil war, with weakened Kurdish forces unable to stop them and a Syrian government in Damascus apparently content to open camp gates and look the other way. The 2014 nightmare, reloaded.

That didn't happen. Not because it couldn't, but because the people responsible for preventing it started working on the problem months before it reached a breaking point.

The fighters are in custody. The biometrics are being collected. The diplomatic cables are going out. The next chapter of this story will be written by whether foreign governments step up or continue pretending their citizens aren't America's problem to warehouse indefinitely.

But the prison break that could have reignited a caliphate? It never came.