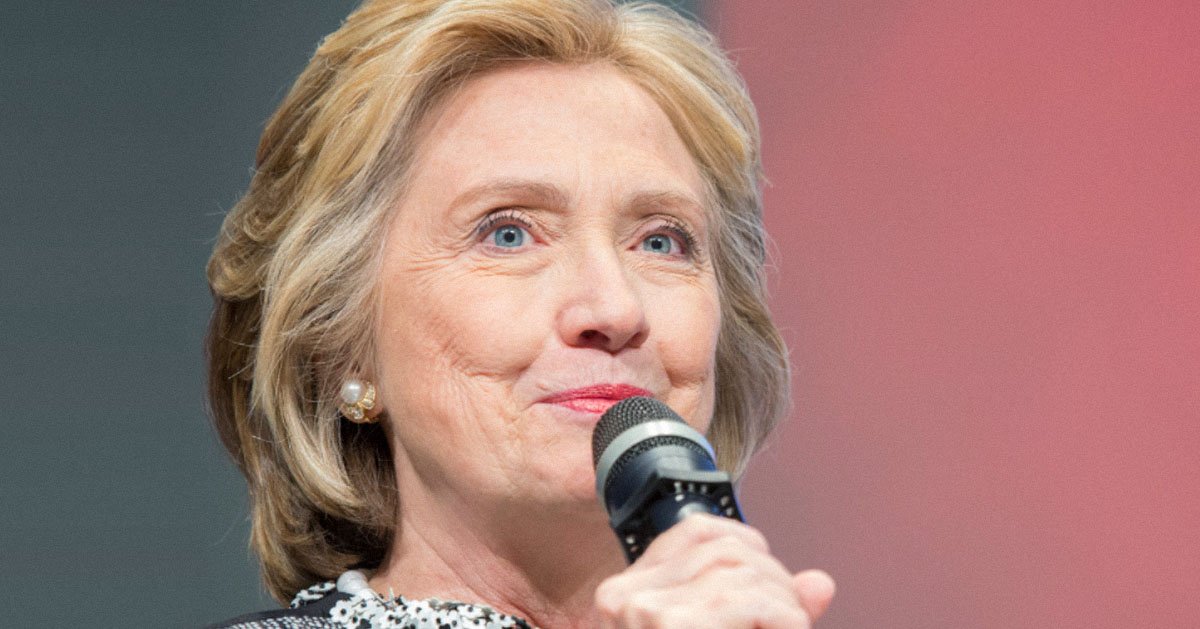

Hillary Clinton told a Munich Security Conference panel that migration has been "disruptive and destabilizing" and called for secure borders — a striking shift from the woman who spent the better part of a decade defending lax enforcement and celebrating illegal immigration as an economic engine.

Speaking on a panel titled "The West-West Divide: What Remains of Common Values," Clinton offered what sounded almost like a concession speech on the issue that helped sink her politically.

"There is a legitimate reason to have a debate about things like migration."

A legitimate reason. As if the debate hadn't been raging for years, while Clinton and her allies dismissed anyone raising concerns as nativist or xenophobic.

She went further:

"It went too far, it's been disruptive and destabilizing, and it needs to be fixed in a humane way with secure borders that don't torture and kill people and how we're going to have a strong family structure because it is at the base of civilization."

Set aside the "torture and kill people" flourish — a poison pill tucked inside an otherwise reasonable-sounding statement. The real story is that Clinton is now publicly conceding what conservatives have argued for over a decade: uncontrolled migration destabilizes nations. She just needed Europe to start collapsing under the weight of its own open-border experiment before she'd say it out loud.

Clinton's Munich remarks don't exist in a vacuum. They sit on top of a long, well-documented record that points in the opposite direction.

During her 2016 presidential campaign, Clinton supported Barack Obama's executive actions deferring immigration enforcement against millions of children and parents in the country illegally. She wanted to end family detention. She planned to continue deporting violent criminals — a low bar — but wanted to scale back immigration raids, the very tool that makes interior enforcement possible, as Fox News reports.

She acknowledged that physical barriers were appropriate in some places along the border, but opposed any large-scale expansion of a border wall. In other words: a fence here and there, but nothing that might actually work.

By 2018, she was on X posting this:

"It is now the official policy of the US government — a nation of immigrants — to separate children from their families. That is an absolute disgrace. #FamiliesBelongTogether"

And then, at the Newmark Civic Life Series in Manhattan, Clinton made the argument even more explicit:

"One of the reasons why our economy did so much better than comparable advanced economies across the world is because we actually had a replenishment, because we had a lot of immigrants, legally and undocumented, who had a, you know, larger than normal — by American standards — families."

So illegal immigration wasn't just tolerable — it was a competitive advantage. That was the position. Millions of people entering the country outside the legal process were a feature, not a bug.

Now she's in Munich, saying it "went too far."

This is a pattern the American public has learned to recognize. A Democrat spends years advocating for permissive immigration policies, attacking anyone who disagrees as heartless, and then — once the political winds shift decisively — discovers that border security was important all along.

Clinton isn't unique in this. She's just the most prominent example. Across Europe and the United States, the center-left is scrambling to reposition on migration because voters have made the cost of denial too high. Elections have been lost. Governments have fallen. The publics of democratic nations have made it abundantly clear that sovereignty and borders are not negotiable.

But notice what Clinton didn't do in Munich. She didn't apologize for supporting policies that contributed to the crisis. She didn't acknowledge that the people who sounded the alarm years ago — and were smeared for it — were right. She simply asserted that the problem exists and pivoted immediately to conditions: it must be done "humanely," borders must not "torture and kill people."

That framing is doing a lot of work. It preemptively casts any aggressive enforcement as inhumane, even as she claims to support secure borders. It's the kind of rhetorical sleight of hand that lets a politician claim the center without actually occupying it.

This is the core contradiction. Clinton says she wants secure borders. Her record says she opposed the wall, backed deferred enforcement for millions, wanted to end detention, and celebrated illegal immigration as economic stimulus. Those positions don't produce secure borders. They produced the exact crisis she now admits "went too far."

You cannot spend years undermining every tool of border enforcement — walls, detention, interior raids — and then claim with a straight face that you're for border security. The word "secure" doesn't mean anything if every mechanism for achieving it is off the table.

Conservatives didn't need a Munich panel to figure this out. They've been saying it since long before 2016, through endless cycles of being called racist for wanting the law enforced. The difference is they said it when it was politically expensive, not when it became politically necessary.

Clinton's remarks matter less for what they reveal about her — she's not running for anything — and more for what they reveal about the broader left. When Hillary Clinton, of all people, concedes publicly that migration went too far, it means the internal polling and focus groups have become impossible to ignore. The Democratic coalition's position on immigration has become an electoral liability so severe that even legacy figures are scrambling to create distance.

But repositioning isn't reform. Saying the right words in Munich doesn't undo years of policy choices that left the border porous, overwhelmed communities, and strained public resources. It doesn't give back the time lost while anyone advocating for enforcement was treated as morally deficient.

The question was never whether migration "went too far." The question was always whether the people in power would admit it before or after the damage was done.

Clinton just answered that.